Shoe Shine

They removed mud and dust, wiped ointments, brushed and polished shoes.

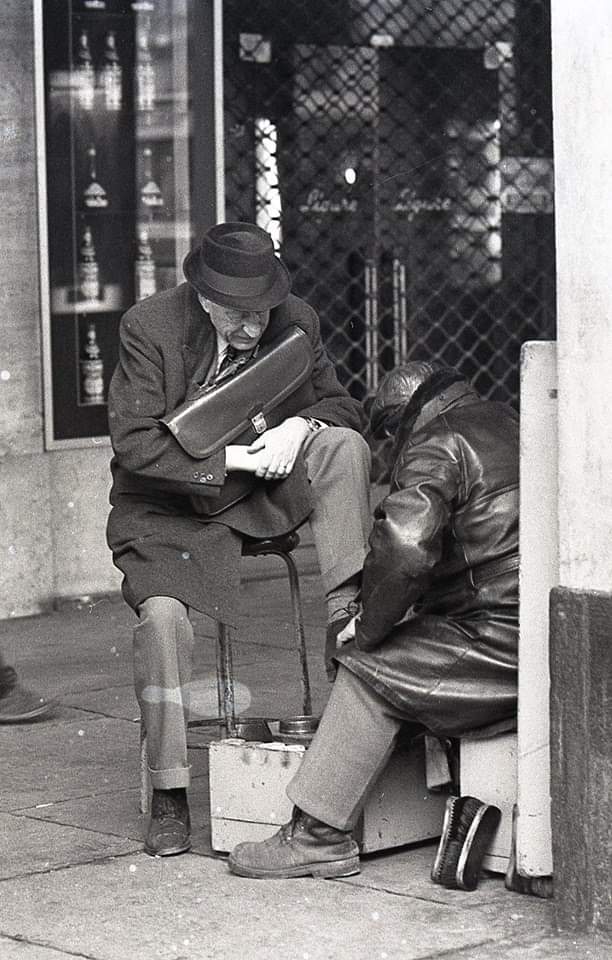

Sitting on a small bench, they positioned themselves in a walkway with the toolbox at the side, arranged a piece of wood on which to place the customer’s foot and waited for the customers inviting them with the reminder:

“Shoeshine! .. Shoeshine!”

After pulling from the box, hard and soft brushes, polish of different colors and a polishing cloth, they began to clean the shoes, caressing them lovingly as if they had a beautiful woman in their hands.

They took possession of the foot and cleaned up the mud and dust they anointed it with a secret mixture, after polishing a shoe with a light touch of the brush on the heel, they invited the customer to extend the other foot, without speaking so as not to disturb him while he read the newspaper. At the end with a vigorous rubbing with the silk of an old umbrella, they warned that the work had been served and received that meager compensation, thanked with a smile.

The shoe shine was a job that many young people carried out in the nineteenth century and which had a strong increase in the post-war period with the arrival of the Americans.

The famous “sciuscià” ( shoosha’) were born in Naples, a dialectal deformation from the English term “shoeshine”.

A job that paid very little but served to feed the family and that De Sica immortalized its existence in 1946 with the Oscar-winning film “Sciuscià“.

A memory of the past, like many other crafts that have disappeared, but which remain the heritage of our tradition and our local culture.

A few years ago Naples bade farewell to the last “sciuscià” Zì Tonino, a reference point for passers-by and tourists from all over the world, with the banquet in via Toledo, close to the Spanish quarters and the Umberto I gallery.

Very few surviving shoe shine though but perhaps there is always someone who, as our ancestors teach, still knows how to transform and reinvent this art.